Contents

If you’re a new writer, or even an old one, (or a new-old one, if you know what I mean!) you would have come across this debate in researching ways on how to write your novel: Plotting vs Pantsing.

You will find articles all over the internet extolling the virtues of each, with each camp often looking at the other as a different (lesser) species of writer.

Now apart from the fact that pantsing is quite obviously a made-up word that makes me want to giggle like a schoolgirl, I don’t have a particularly strong opinion on the subject. This might surprise you, given that I am about to offer you the ultimate guide to plotting versus pantsing.

You will also discover that, as with most things in life, there exists a very healthy spectrum of grey in between this black and white simplification. This article will explore not just plotting and pantsing (I’m still giggling) but also that world that exists where you can utilise the strong points of both.

Firstly, let’s dive into definitions of each:

Pantsing

What is pantsing?

Pantsing is unsurprisingly, the act of sitting down and writing, quite literally, by the seat of your pants.

The cliched version of this will see you opening up your laptop, or sharpening your pencil in that decisive way that you do, and then start to write with no forward planning, no idea of where your characters or story will take you.

It’s the picture that is most often used in Hollywood; it also happens to be the one that serves up the most drama when illustrating writer’s block. You know, the one where the writer is sobbing over a blank page when the words don’t come.

Most pantsers concede that they will have SOME idea of what they’re going to write, whether that be one particular scene that starts everything off, or an idea for a character or two, but pantsers do NOT plan ahead. Instead, they let each sentence take them onto the next.

Stephen King, the most famous of pantsers, says he likes to put characters in a stressful situation and see what story emerges. I dare say it has worked out ok for him.

Plotting

What is plotting?

You can imagine that plotting is the complete opposite.

Also called outlining, it involves a process where you create a structure for your novel before you write it. You write headlines for the major plot points of your novel which provide a map by which you navigate your way through, filling in the detail as you go.

Of course plotters all plan and plot to a different extent. Some will start writing their novel having just the beginning, middle and end in mind, others have written outlined drafts of their novel that consists of up to ten thousand words.

One of the most famous plotters, who also happens to be the top selling author of our time, is James Patterson.

His outlines are quite extensive and read like little stories by themselves.

Quite accidentally, (maybe) my two examples of pantsing vs plotting have a bit of history between them, with Stephen King famously saying James Patterson is a terrible writer and the latter then writing a book called ‘The Murder of Stephen King”. (The book launch was cancelled)

If anyone cares, I happen to think they’re both brilliant.

Why the debate between Plotters and Pantsers?

I believe the debate arises for three reasons:

1. Humans like to belong to a group. This is yet another group they can belong to and create delicious division where there does not need to be any.

2. Humans like to think the art they create is a form of magic.

Pantsers = Magicians

Plotters = Mechanics

This comes from that feeling you get where a line of dialogue jumps into your head, or a particular turn of phrase comes from seemingly nowhere and you just have to put it into your story. Not to mention those times where you woke in the middle of the night with an idea, feverishly tapping away on your keyboard before the magic left you as quick as it appeared.

I happen to think there is nothing magical about it, even though it may feel like it, but I’ll reluctantly leave that debate for now. The point is that the somewhat more methodical way of plotting your novel is seen to be a threat to the magic, either getting in its way, or producing an inferior story.

Us writers are a funny bunch.

On the one hand, we can be extremely supportive of each other, giving advice whenever it’s asked for and generally being good guys. On the other, the ones with a few novels under their belt can suffer from delusions of grandeur, believing themselves to be above the afore-mentioned mechanics and scoffing at the idea that there can a be “process” for writing a good story.

3. There is money to be made.

Let’s face it. You can’t write a book, sell a course, or run workshops on the magical bit. If writing a novel was just about having an idea, sitting down and writing it, there would be a tonne of people not making money out of those keen for a manual on how to write the next bestseller.

Remember at this point I’m still not arguing for or against.

I’m just saying that the plotters have a financial incentive in this debate, as cynical as that may seem.

But hang on, before coming to a verdict, let’s discuss in more detail the various methods employed by plotters and pantsers.

Ways to pants your novel:

I have already mentioned that the most common version of pantsing involves no planning whatsoever. The writer sits down and away he goes, a novel emerging at the end.

But of course there are a variety of ways that pantsers approach writing, and very few of them write in quite the way you might expect.

1. Write with a few key scenes in mind:

Think of your potential story and try to imagine a few key scenes. These can give you a starting point, or a point you could aim towards.

Either way, a sense of the mood and genre should come to mind, as well as a hint of the characters that would take up the stage.

2. Write forwards, plan backwards:

The always excellent, and as it turns out pantser, Emma Darwin, writes that she feels there is nothing wrong with letting your dreams and imagination take flight on that first draft. Then having done so, you can ‘plan’ backwards, now having a better idea of what it is you’re creating.

She also rightly points out that there is a risk with this method that you could become too attached to your scenes and characters, making it very difficult to go back and get rid of things that don’t work.

That does not mean the method is not legitimate, but just that you would need to develop the cruel and necessary ability to ‘murder your darlings’.

3. Start with a character:

Take a character and start writing the story from that character’s point of view, letting their voice and actions guide you.

Take a character and start writing the story from that character’s point of view, letting their voice and actions guide you.

This method is often associated with those that say a character speaks to them. Yes, essentially, that they are hearing voices! (The magic is strong in these people:)

If this is you, I get where you are coming from. There are times when a character says and does something that surprises you (or are you just surprising yourself?) and can take the story in a whole new and unexpected direction.

4. Start with a scene:

Choose the most important scene, the scene that embodies the story and it’s conflict, and write that one first.

This will give you something to hang your hat on, a feeling as to where your story will be heading and an overarching conflict that can drive all other actions.

Plotting in disguise?

Even as I write this, I can hear the naysayers among you whisper, “Isn’t all of this just a little…erm…plotting?”

I’ll avoid eye contact with you as I answer, my eyes will dart up and to the left and I’ll say, “Of course not.”

We’ll get back to this, but for now, as there is almost by definition no specific way to pants, it might be helpful to think of pantsing in terms of helpful tips, so here are a few:

A few helpful tips for Pantsers:

- Whatever you do don’t stop. If you’re going to pants, go all in. Don’t worry about your adverbs and adjectives, your show or your tell. Just write. Put your wildest flights of fancy down on that paper or on that laptop screen and do. Not. Stop.

Imagine you are the modern day equivalent of Arturio Bandini, sweating and slaving over your manuscript, getting it all out until  you’re spent.

you’re spent.

Write as if your career depends on it, which might very well be true.

2. For that first draft, forget continuity, forget plot. Instead, use the narrative and dialogue to drive your story forward. This may very well mean you follow every rabbit trail that presents itself. Do it.

Down these rabbit trails is where you’ll find the magic.

3. Know your genre. This means that you will loosely know the conventions that your readers might expect. A hero or heroine. Action and tension. Twists and turns. Whatever your chosen genre is known for.

You’ll have them in the back of your mind as you write, and they will subtly help shape your story.

4. Do not edit. If it helps you get back in the flow, maybe. But your inner editor is not the same guy that brings the magic. You have to shut him up on that first draft, maybe even the second.

5. Don’t stop to find out if 19th-century monks had mobile phones, you can do the research later. Make a note of the sticking points if you have to, but pay them no heed. Later drafts are where you get technical if it’s needed.

6. A cool tip, and one quite a few famous writers employ, is to purposely stop mid-sentence or mid-paragraph, in order to save some precious flow for the next time you write.

Ernest Hemingway said, “Stop while there is still more to be said.”

Which, when you think about it, means there is more to that quote than we know!

7. When you get stuck, and you WILL get stuck, jump to a few scenes ahead, or if things are really bad, to a scene you’ve been keeping for rainy days (I.e this moment)

This elusive thing called “flow”, closely related to the other elusive thing called “magic”, can really leave you as quick as it arrived, so for those moments, you need to plough ahead with the knowledge that it will return.

Ok so having got that out of the way, let’s say goodbye to the magicians and talk about the mechanics.

The plotters, the planners, the ones with spreadsheets and spanners.

The plotters, the planners, the ones with spreadsheets and spanners. Click To Tweet

Ways to plot your novel:

1. Outlining vs Structure:

The first thing to note is that talking about outlining is not the same as talking about story structure, though hardcore plotters might plot with the story structure in mind.

I’ve already explained what plotting is, but a story or narrative structure is based on the belief that all stories (the ones worth telling anyway) follow a shared structure.

Some talk about a three act structure, others about the 5 key turning points in a novel, but basically it refers to key elements that are present and have been present in storytelling since mankind sat around the fire, drinking curdled milk and re-telling the action of the day’s hunt of a woolly mammoth.

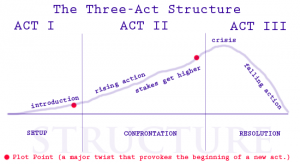

2. The three-act structure:

The most common story structure that originates from the early theatre and is most often used in screenwriting, is called the 3-act structure.

The most common story structure that originates from the early theatre and is most often used in screenwriting, is called the 3-act structure.

Any story is divided into three relatively distinct parts, the Setup, the Confrontation and the Resolution.

The first act is used to set the scene and world in which the story will take place, establishing the characters and their relationships with each other and the environment they find themselves in.

This act will include what’s called the ‘inciting incident’ or ‘catalyst’. Something will happen towards the end of the first act that provides the drama and poses the question, “What will our main character/protagonist do to save the day?Restore things to the way they were?”

The second act contains what’s called ‘rising action’ and basically describes the protagonist’s attempts at fixing things, only to find the opposite happening. The main dude/dudette does not have the skills to overcome the forces of the antagonist and must acquire these skills, resulting in a kind of progression called the character arc.

The best stories have pretty cool arcs.

Act three is the resolution and contains the climax, where all tensions are brought to their highest point before being resolved. The main characters are left knowing themselves a bit better than they did in act one.

The sharpest among you will have realised I’ve just told you a story has a beginning, a middle and an end. Oh and that it needs a bit of drama. Duh.

But can you see that if you were to plot your story before you wrote it in earnest, it would be good to keep the above in mind?

3. Story Grid:

There are of course variations on the three-act structure, an interesting one being Shawn Coyne’s Story Grid.

The Story Grid is both a diagnostic tool and a structure, based on the way that an editor would see your manuscript, with a

Beginning Hook, Middle Build and Ending Payoff. Find out more here.

4. The Snowflake method:

Unsurprisingly, the snowflake method is based on the principle of snowflake fractals.

You would start with writing one sentence (a short one) that sums up what your story is about.

For the next step, you’ll expand that sentence into a paragraph which will give you a kind of informal synopsis.

After having done this step you’ll do the same paragraph summary of each of your characters describing their motivations, goals and conflicts.

At this point the method asks you to expand on your original synopsis and then grab a spreadsheet, yes I said a spreadsheet! On this spreadsheet, you will enter single lines for each scene and then expand on those etc.

The idea now is that your novel keeps growing in size, with more and more detail being added until you have the finished draft.

Randy Ingermanson does a much better job of explaining it on his site, Advanced Fiction Writing.

5. The Hero’s Journey:

Joseph Campbell thought that all world myths contained a similar narrative. Again, just like the three-act structure, we have in this case:

Departure or Separation, Initiation and Return.

In the Departure, the protagonist receives a call to go and do something epic. He refuses. He is then persuaded by a mentor or supernatural wise-guy. (Think wizard) and enters the second stage.

In Initiation, you guessed it, our hero goes through trials, temptations and tribulations, almost dying in the process but evolving into a bad-ass. The good kind of bad-ass.

Finally, in the Return, the protagonist returns to the problem at hand and though it’s close, emerges victorious.

One of the most popular examples of this is Star Wars, with George Lucas citing Joseph Campbell as an influence.

6. The Freytag method:

As no-one can agree on numbers, it’s no surprise that there exists yet another framework, this time one that has five parts. Inflicted upon the world by Gustav Freytag, these parts comprise exposition, rising action, climax, falling tension and conclusion.

Though existing of more parts than the three-act structure, the Freytag outline model weirdly allows for more freedom and only a loose sense of structure.

7. The James Patterson method (for want of a better term)

As I mentioned in one of my first posts on this blog, my writing journey started with a Masterclass with James Patterson. Whatever you may think of his writing, suffice to say I still watch those videos to feel inspired. The man loves writing and it’s infectious!

His method, though not as official as others, is to plot to great detail every scene of your novel. The plot will read like a complete story and should grip you as much as the actually completed draft will. His outlines will often span 10 000 words or more.

A few helpful tips for Plotters:

- Write a script – your very own film:

It might be useful for some to write the entire novel as a screenplay, I.e. description – dialogue – repeat.

You can then go back and turn all of this into prose. I’m intrigued by this idea as it’s so character focussed yet allows for story to unfold, without being bogged down by the need to be poetic.

2. Index cards:

If you’re going to plot, go all in! (Have I said that before?) Write the bare bones of each scene on an index card to enable you to shift things around and get a great overview of how the plot could fit together. Of course, the digital version of this would be something like the corkboard in Scrivener, an absolutely invaluable tool in many a writer’s toolbox.

3. Mindmap:

Another cool thing to do is to map out plot ideas along with characters on a big piece of paper, a kind of stars and planets thing that will help you connect the different themes and players visually.

For this purpose I use Scapple. Actually, I use Scapple for a ton of things, it’s endlessly useful.

4. Spreadsheet:

I will write about this in detail at some point, but suffice to say that the good old spreadsheet has many, many uses! Especially for something like a thriller, plotting out your scenes and character arcs on a spreadsheet is absolutely brilliant in making sure you don’t lose the plot. (Sorry!)

5. Outline in reverse:

Start with the ending and plan how things would have had to progress to get there. Similar to the pantsing idea of choosing a scene and writing around that scene.

6. Structure each scene:

Anastasia Parkes says all scenes should read like sex, meaning they should include foreplay, action, climax and wind down.

Did I mention she writes erotic fiction? Still, can’t argue with her advice!

Additional Considerations:

Discipline:

My personal view is that if you’re someone who struggles with personal discipline or at least finds it difficult to concentrate for long periods of time, plotting might be the way forward.

Essentially you’ll have this framework that will survive periods of disruption and will give you a roadmap that you can use to find your way back into the novel when either, your mind wanders, or you can’t write for a decent amount of time in one sitting.

Mood:

Following on from the above, it seems that when inspiration strikes and the stars align perfectly, one can sit down and pants your way through a 100 000 word manuscript. This implies a certain state of mind, and for want of a better word, a certain ‘mood’.

The reality is that, for a lot of us, that mood is very difficult to cultivate or wait for. The normal stresses of life, work and kids mean that writing can be quite a fragmented exercise, to the extent that once you find precious time to sit down and do the business, you’re not in the mood.

So for those times, it helps to have a structure in place that leans heavily on previous moments of inspiration, where the mood WAS right and you plotted out your novel knowing times might get tough!

Genre:

When this discussion around plotting versus pantsing comes up, a point that is often made is that your chosen genre might play a role in deciding which method to use. As Russel Blake says, “It’s hard to write a whodunnit if you don’t know whodunnit.”

So for instance, genres of crime and thrillers, fantasy and science fiction might benefit from plotting, but certain styles of literary fiction and romance perhaps not.

Outliers:

Another important point to make is that defenders of either method often make an appeal to authority. E.g. James Patterson is a best-selling writer, he plots, so if you want to have your books sell, so should you.

Stephen King, a best-seller and a great writer that inspired some of the best films of our generation, is a pantser, so you should be one too.

Can you see how ridiculous this is? Especially when you consider that writing styles differ wildly from author to author, and that each has a measure of success that might not be yours.

Further, the concept of outliers plays a role here. Stephen King might scoff at the idea of plotting, but he might (and probably does) have the innate ability to write a story that has all the requisite plot points without having to think about it.

Further, the concept of outliers plays a role here. Stephen King might scoff at the idea of plotting, but he might (and probably does) have the innate ability to write a story that has all the requisite plot points without having to think about it.

Most ‘normal’ writers might not. Don’t forget that Mr King spent years and years honing his craft, and STILL writes the odd flop…something to think about?

Conclusion:

So here is my personal take:

There is no debate, there is no conflict.

I’ve essentially just written a 3500+ word article to describe the differences between the two camps when really, I don’t believe there is a difference.

It’s all the same thing.

The difference, if there is one, lies not in the ‘how’, but in the ‘when’.

Plotters are pantsing, but they do the pantsing in advance and/or as they go.

Pantsers are plotting, but they do it as they go, or after.

BOTH methods arrive at a point, maybe midway through the first draft, at the end of that draft, or maybe even at the end of a second draft, where they have a big lump of a story that now needs refining and sharpening into a real story.

At this point, the pantsers will work on their plot, the plotters will re-plot or work on their character arcs, strengthening elements of theme and emotional engagement.

Could all of this be as simple as explaining the difference between those who like to go walking the woods with no map, but then have to find their way back, versus those who like to know where they’re going, but will veer off course if they feel like it?

Is the difference just one of personality? What do you think?

P.S. Guess how I wrote this article. Damn right, I plotted the hell out of this puppy!

P.P.S. If you found this post useful, entertaining, or it tickled your fancy in ways unimaginable, please consider sharing it via the very helpful buttons below!

Recent Comments